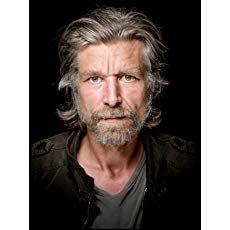

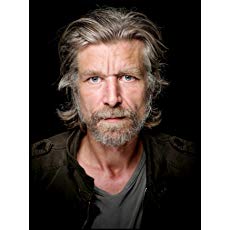

-The author, Karl Ove Knausgaard

-The author, Karl Ove Knausgaard

Perhaps the greatest joy of reading, beyond escaping into the story itself, was discovering your self in another person’s words and worlds. Realizing that you were not too idiosyncratic. Not unusually unusual. That others, a certain few, thought as you did, felt things deeply or, as likely, not at all. These characters possessed your attributes and defects. They were outcasts. Geniuses. Drunks. Fathers. Husbands. Monsters too. Books opened doors where before you’d only glimpsed through keyholes. They validated you, even if in unsavory ways. Bram Stoker’s Dracula seduced you as the vampire seduced his prey. Inflamed by Ayn Rand’s iconoclastic hero Howard Roarke, who steadfastly zigged against a tide of mindless zagging. Hemingway’s Old Man and the Sea beguiled you. “Fish… I’ll stay with you until I am dead.” Your heart beat madly as Kurtz’s in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. You, too, were “loyal to the nightmare of your choice.” Here, finally, was the other. Here finally were you.

Most recently, you’ve been reading (more like devouring) the auto-fiction of Norwegian writer, Karl Ove Knausgaard. His epic and massive series, My Struggle is, for you, nothing short of transcendent. Beyond memoir, Knausgaard vivisects his persona, revealing the truth about himself and those in his orbit, with intense clarity and unimaginable attention to detail; it is an autopsy of self, but never dour. On the contrary it is lightness itself, like a bright conversation. Somehow, someway, he illuminates the mundane, making it into something incandescent. Hard to explain but easy to feel. Brutally frank, regardless of the pain and embarrassment his admissions ultimately caused to both the author and those closest to him; his revelations strike you as necessary, even inevitable. In doing so, Knausgaard may have enraged his loved ones (you have read as much online), but he helped you to understand yourself, your defects and virtues, as never before. You relate to so many passages, choosing one is like picking out a goldfish at the pet shop. This, from his book Spring (part of a series he wrote just after My Struggle), speaking to his infant daughter:

I’m not good enough at talking to people to have close friends, and then there is also that I spend all my time on myself, which people notice, of course, so that no one takes that extra step. If someone does attempt to get closer, I usually withdraw into myself. That’s how your father is, a little shy of people, not necessarily because I want to be that way, but because that’s what I have become, and because that life, alone in front of the keyboard and the computer screen, is easier.

You could have written this to your daughters, every word. “It’s not a good quality,” he writes, “but it will become part of your life…I am writing this as an apology to you.”

Not sorry enough to change, however. And neither shall you. Some of it is laziness born of fear –call it wariness- but your questionable behavior, you’ve come to realize, is merely accepting the things you cannot change. Knausgaard is, at his core, an introvert and a narcissist, And so dear boy are you.

Interestingly and regrettably, it is precisely these two traits that define so many notorious killers. Ever since reading Truman Capote’s seminal book, In Cold Blood, you’ve identified with pathological murderers and are drawn to the genre because of it. In particular, it is the serial killer you find most compelling. Ted Bundy. Jeffrey Dahmer. Zodiac. Like the vampires you adored as a youth, here were real-life loners who craved attention in the worst way possible. Introverted and narcissistic, each man was an egomaniac with an inferiority complex. Their cruel egos got the better of them. It stopped others cold.